AX: Building Empathy and Intuition for Agents

Imagine discovering a popular GitHub repo, finding an issue, deciding to help out and solve it. You write your code, open a PR and get reviewed. Now imagine doing that only through APIs. That would suck. That is MCP.

Imagine I let you use a desktop but I only give you a screenshot every two seconds. And you can only tell me a single button to press in-between. That would suck. But that is computer-use today.

These aren't good human user experiences. So why do we give them to agents? Agents who are, by most measures, worse than us at these tasks.

This is the premise of AX - a exciting concept. Today I want to introduce it to you and use it to build your agent empathy and agent intuition, so you can make powerful agentic harnesses.

But first, to show you it matters: It's Opus 4.5 release day - a mega-impressive model. Hidden in its system cardRead the full Claude Opus 4.5 System Card. is a note from an internal Anthropic survey: "What would Anthropic employees rather lose, Claude Code or Opus 4.5?"

The harness is where capability becomes output: optimised tools, prompts, and environments unhobble a model's intellect, they extract reliability and agency. They let the spice flow.

Building Empathy for Agents

The best prompting advice I've ever heard is to build empathy. Have someone give you their prompt - ideally one AI struggles with - and see if you can perform the task. I'll make the same ask of you when designing agents.

That's it. Put yourself in the model's position. Experience the constraints it experiences. See what it sees, nothing more. I've even created You Are An Agent, a game I made for you to build experience:

This last year I've continually watched most people skip this step. It's easy to write a harness without experiencing the pain of using it, imagining execution with all the context in your head. Then being surprised when the model "doesn't follow instructions" and "blows up its context".

But situational empathy will only get you part of the way. At the end of the day you're still simply not an AI-they're a different type of being. They don't have five senses, they experience the world in a fundamentally different way. Try to imagine it:

- Imagine you have simultanagnosia, a neurological condition. You can see a fork. You can see a knife. You cannot see "a fork next to a knife." Each object resolves fine in isolation; the spatial relationships between them don't. That's roughly how models see: the image gets tokenized into lots of little local views, and the model has to reconstruct relationships from them. They often get spatial reasoning wrong - not because "next to" is hard, but because the visual evidence has to be assembled across tokens and attention doesn’t always land where it should.

- Or imagine you're fluent in English but you never learned to read. Words are sounds with meanings. "Strawberry" is a thing you say, not ten letters in a row. If I ask how many r's are in strawberry, you'd have to slowly sound it out, counting on your fingers, and you'd probably get it wrong. That's how models read-tokenized-seeing "straw" and "berry" as irreducible units.Try it:

3214b8ea-325b-4943-b6f1-14d9fc037743- Claude sees 24 tokens, GPT-4o sees 22, Gemini sees 35. Same string, different perceptions. The letters inside aren't perceived. They can learn to work around this. But it's a hack, not sight.

The point I'm making here is that situational empathy is necessary but insufficient. You also need an understanding of how an agent sees the world, and an intuition of what action it will take.

If I challenged you to build this psychological model for a human you'd ask me the same questions I'm about to ask you: How were they raised? What were they taught?

For agents, we need two more questions: What limitations have they been hobbled with? And-perhaps most important, given a new model drops every quarter - what's the path of their "improvement"?

Building Intuition for Agents

We’re watching human interface history rerun on fast-forward. Your UX intuitions from living through desktop → mobile → touch → voice are useful because AI is taking a similar trajectory (unsurprisingly, it did learn from us). But - AI has different innate capabilities and failure modes. It can clone itself at will, swallow 200k words, watch a whole movie instantly, and yet it can't count letters. It has no genetic builtins, no universal gestures, no innate spatial reasoning. So while the trajectory has been familiar so far, now we’re reaching the fork where we must design for the machine’s nature, not ours. Let's walk down towards that fork together:

Fixed Function

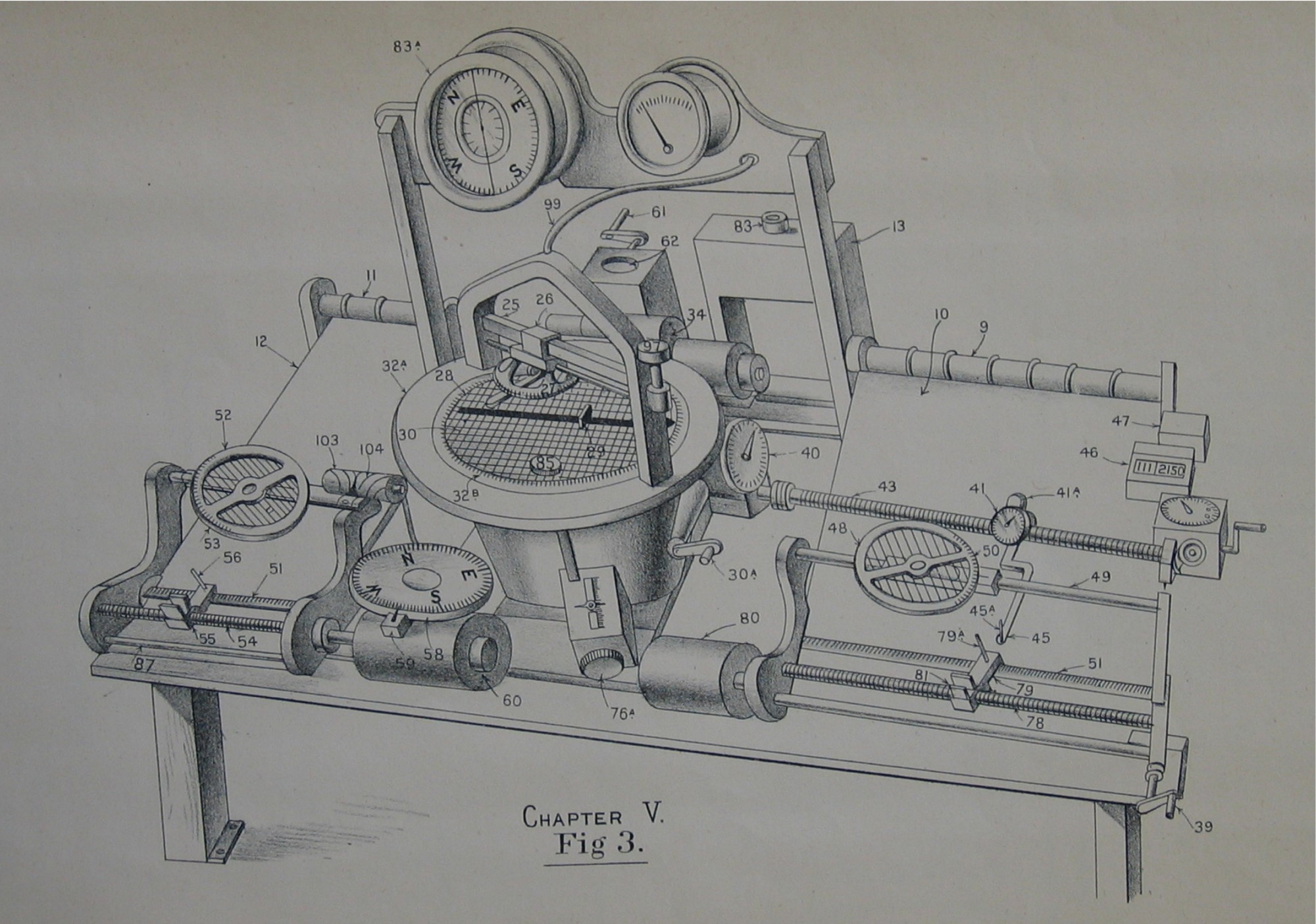

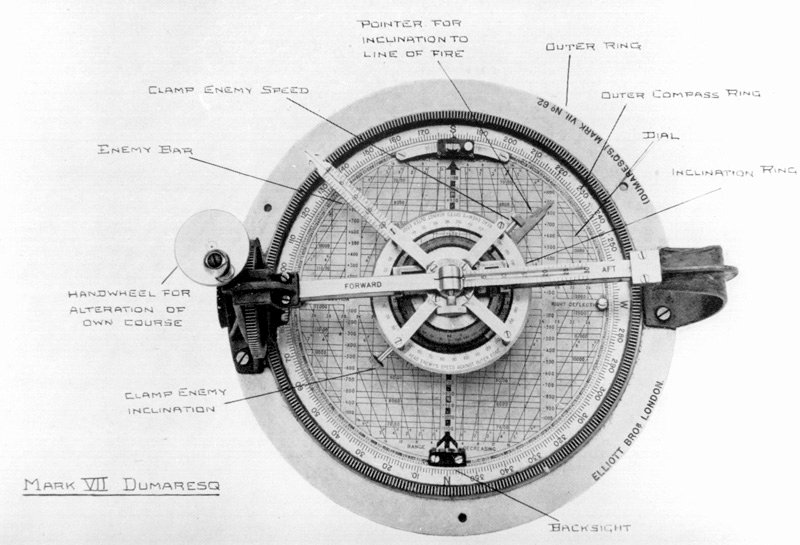

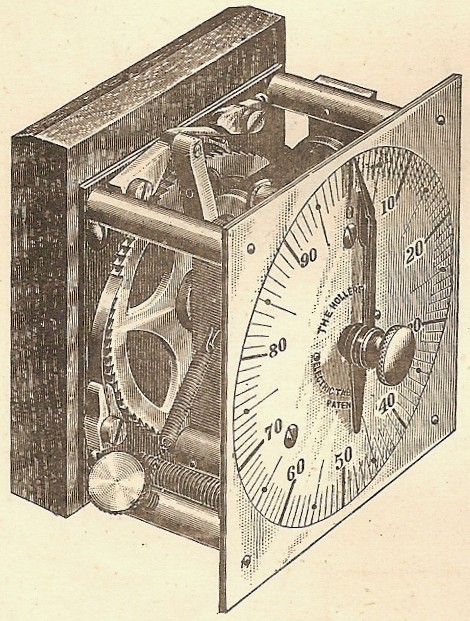

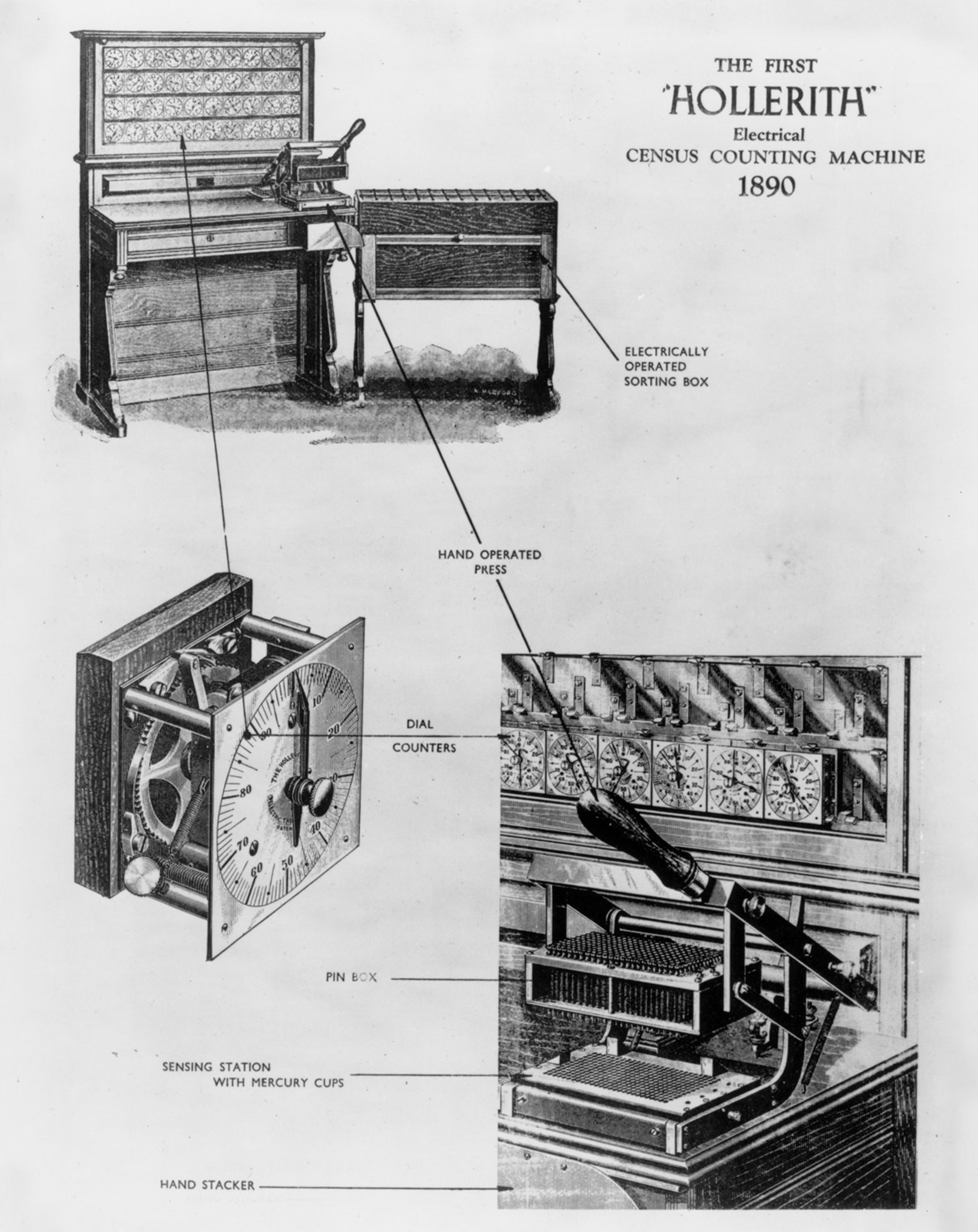

Our earliest computers could only perform fixed actions. The Hollerith Tabulator (1890) added and subtracted, counting census cards. The Dreyer Table (1912) integrated, multiplied and divided numbers, calculating naval gunnery firing solutions. Results appeared on classical interfaces - dials and mechanical counters - the display was as fixed as the functionality.

Agents reached this stage in 2023 with tool calls - ChatGPT Plugins, function calling APIs.

Programmable

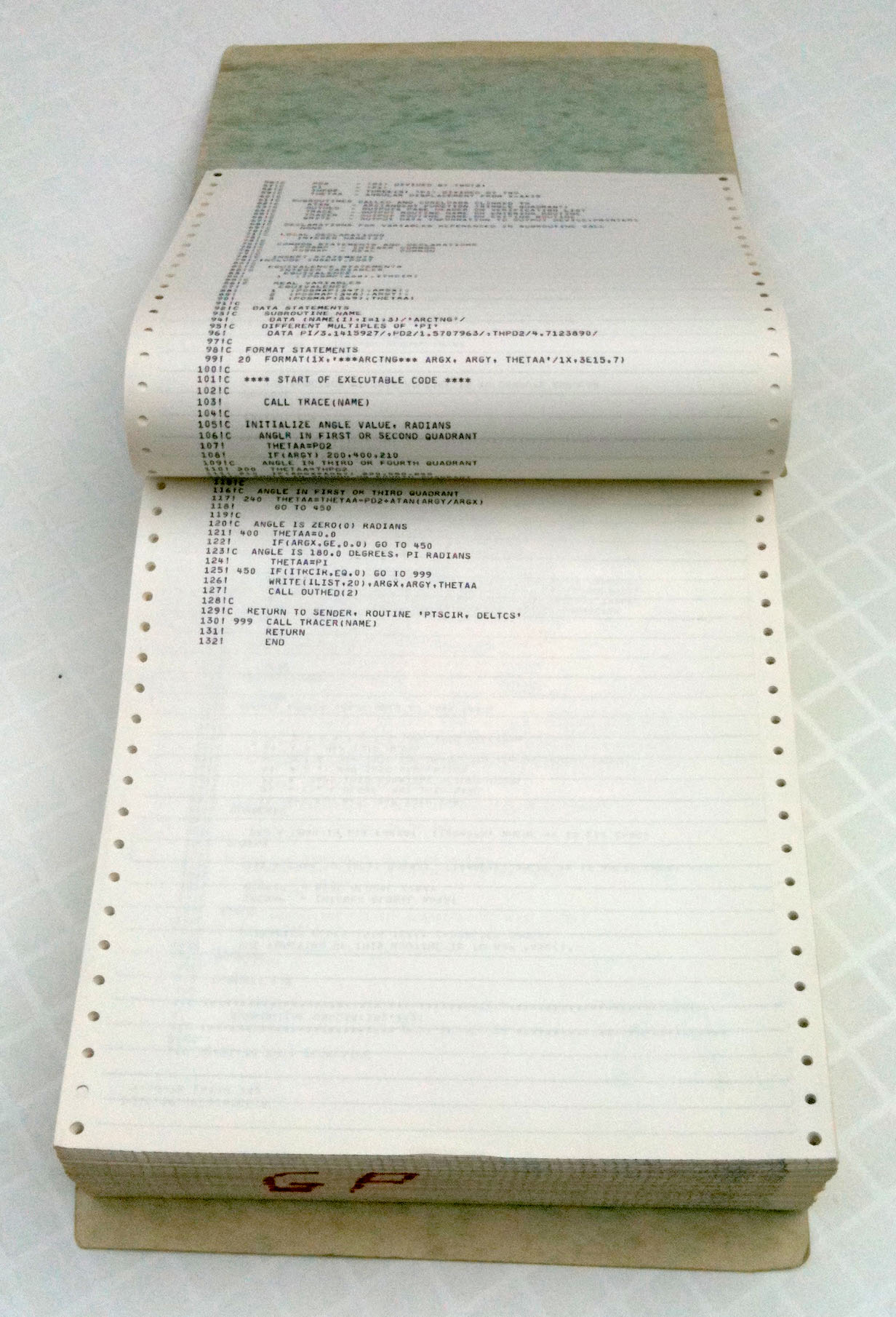

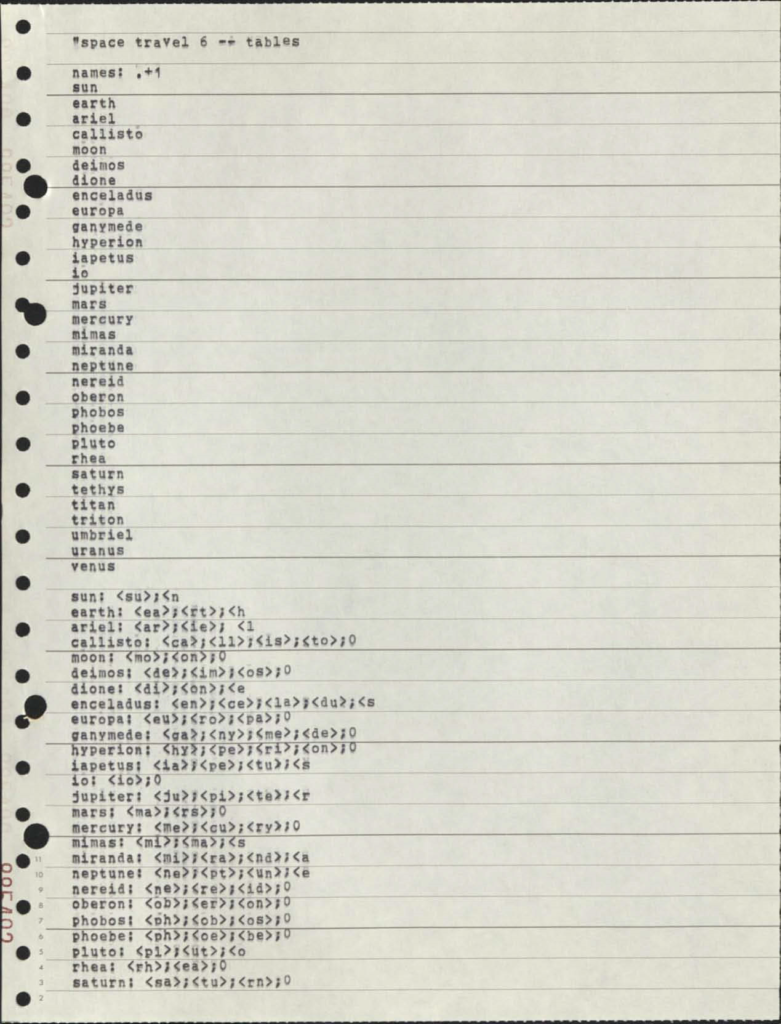

Then we invented programmable computers: ENIAC (1945), UNIVAC I (1951). You could write an arbitrary program, run it, and receive your results printed onto reams of paper and flashed through bulbs. We escaped the limitations of fixed interfaces, but state didn't persist. If you want to build on what you did, you're basically starting over, or you're manually copying outputs into new programs.

Agents reached this stage in 2023 with Code Interpreter, Claude Artifacts.

Interactive + Persistent

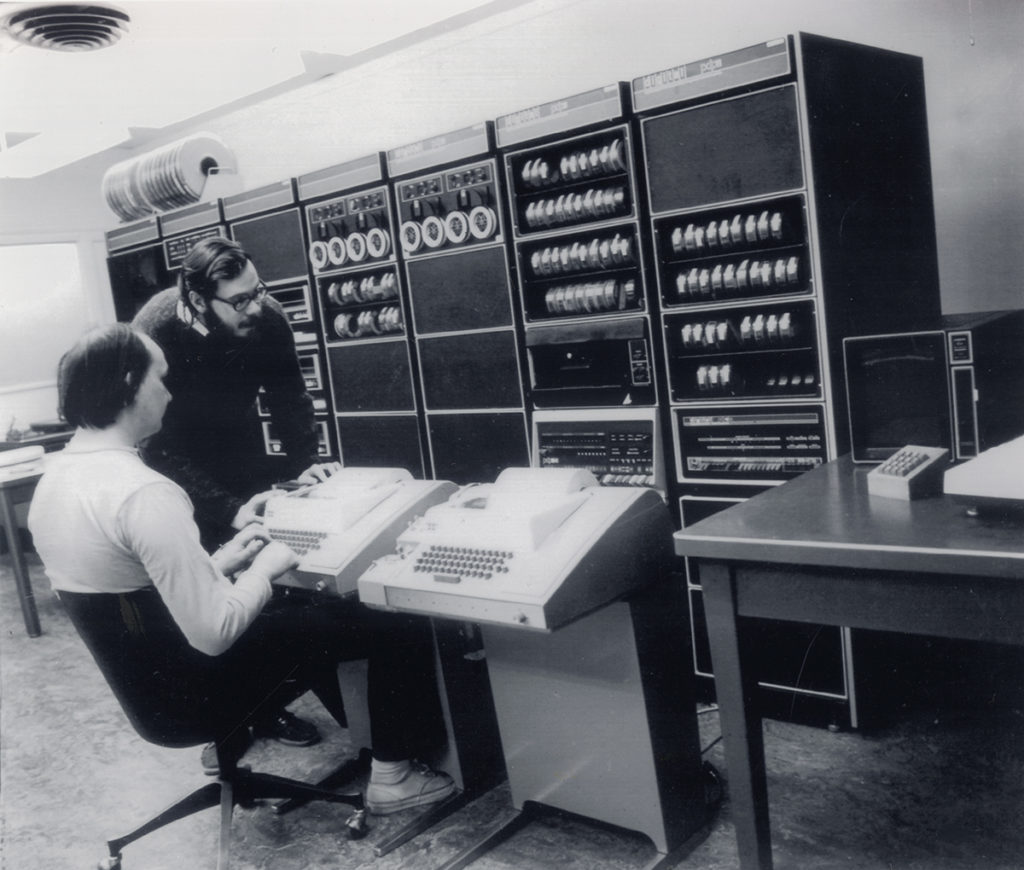

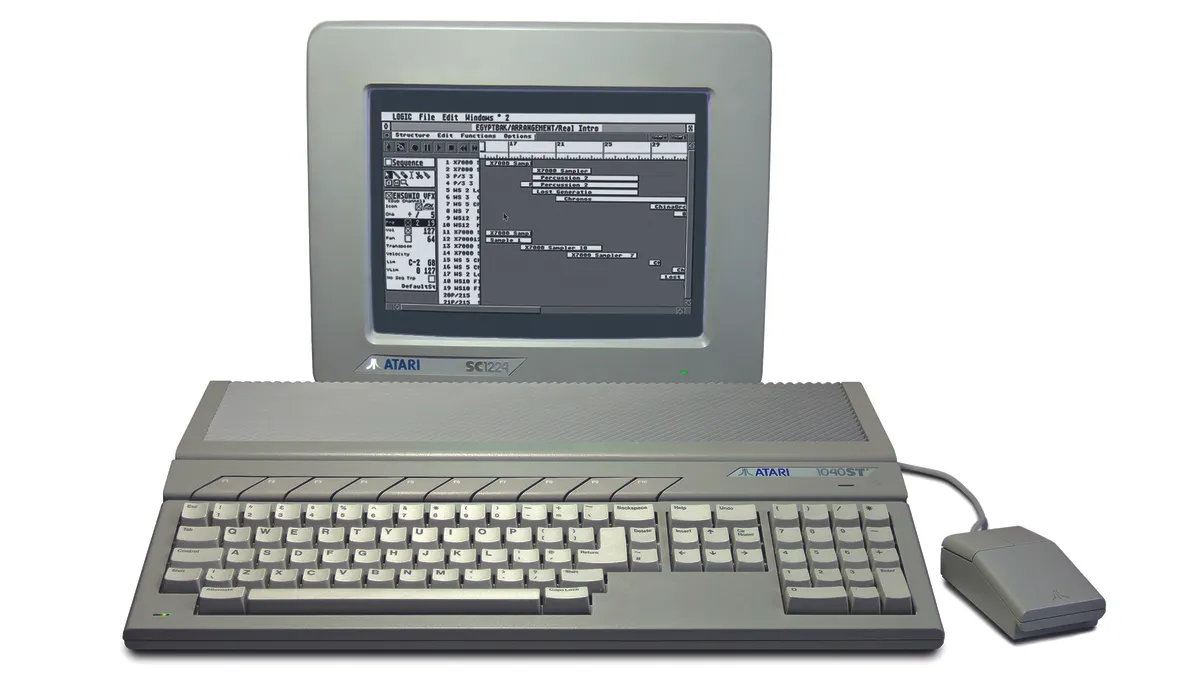

Then came interactivity, composability and persistence. The PDP-11 (1970), Unix (1969). Digital text displays and operating systems that merged the punch card UX (for writing code) and the paper printer UX (for reading outputs) into a single visual interface. Small displays meant every single character had to count - we designed UX where nothing was wasted. Command lines gave us composability: feeding one program's results into another, avoiding manual reading and rewriting. File systems gave us persistence: you could come back and work on tasks days later and your files were still there. Folders and directories gave us structures that humans intuitively could work with.

Agents reached this stage in 2023 with long running agents using bash, file systems - Cursor, Claude Code, Codex.

Visual Interfaces

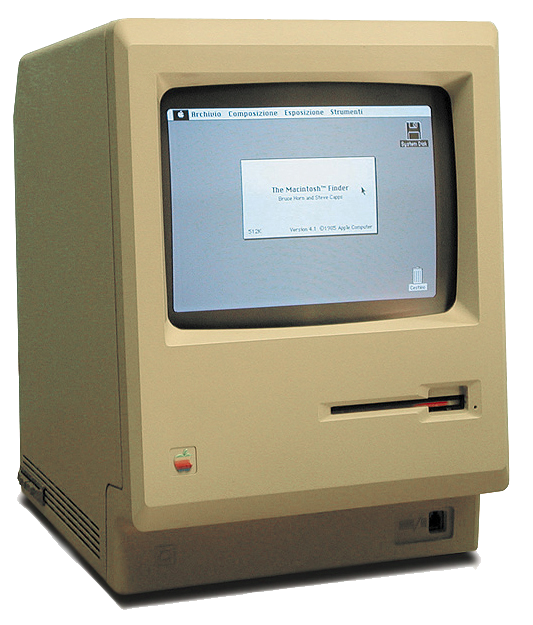

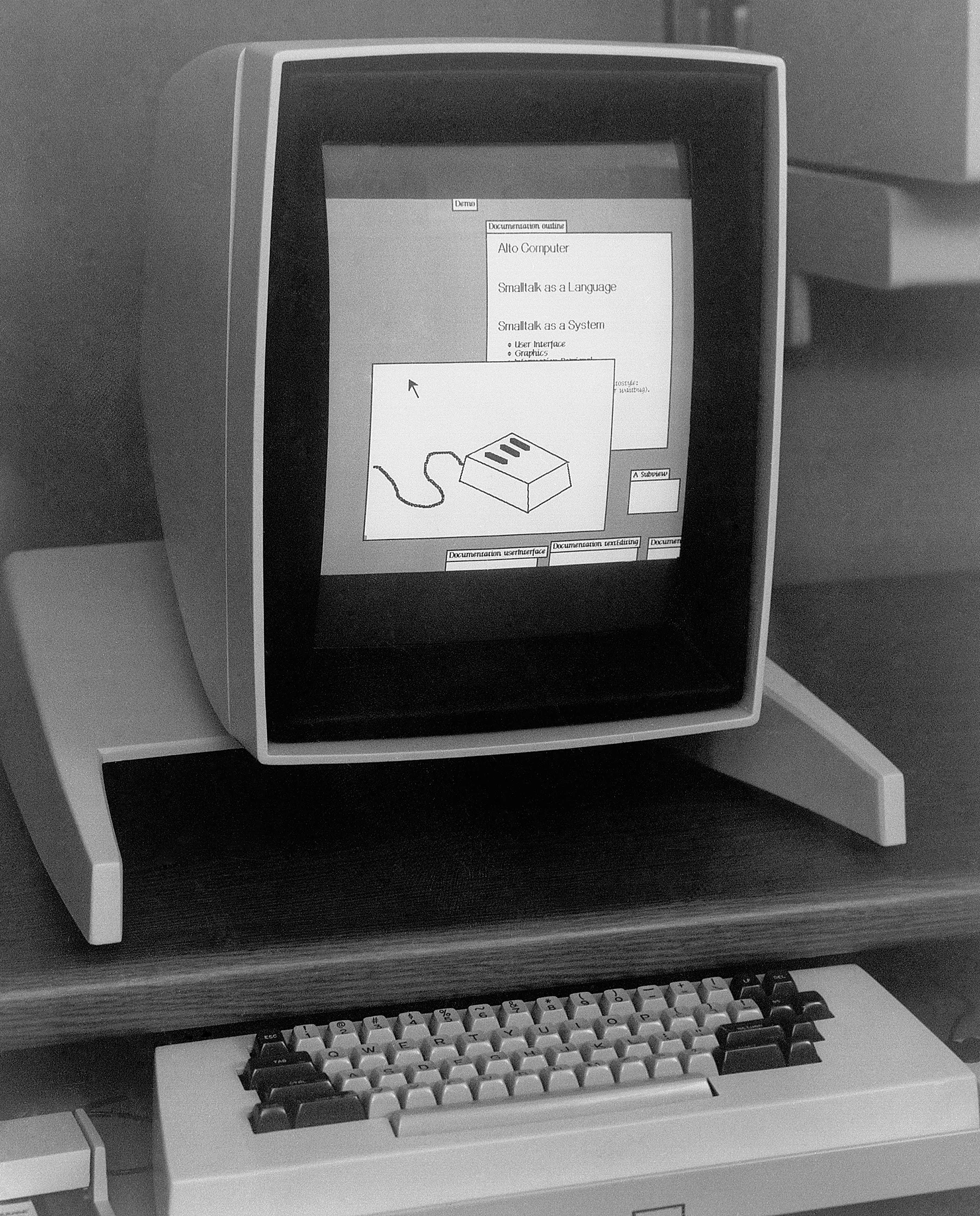

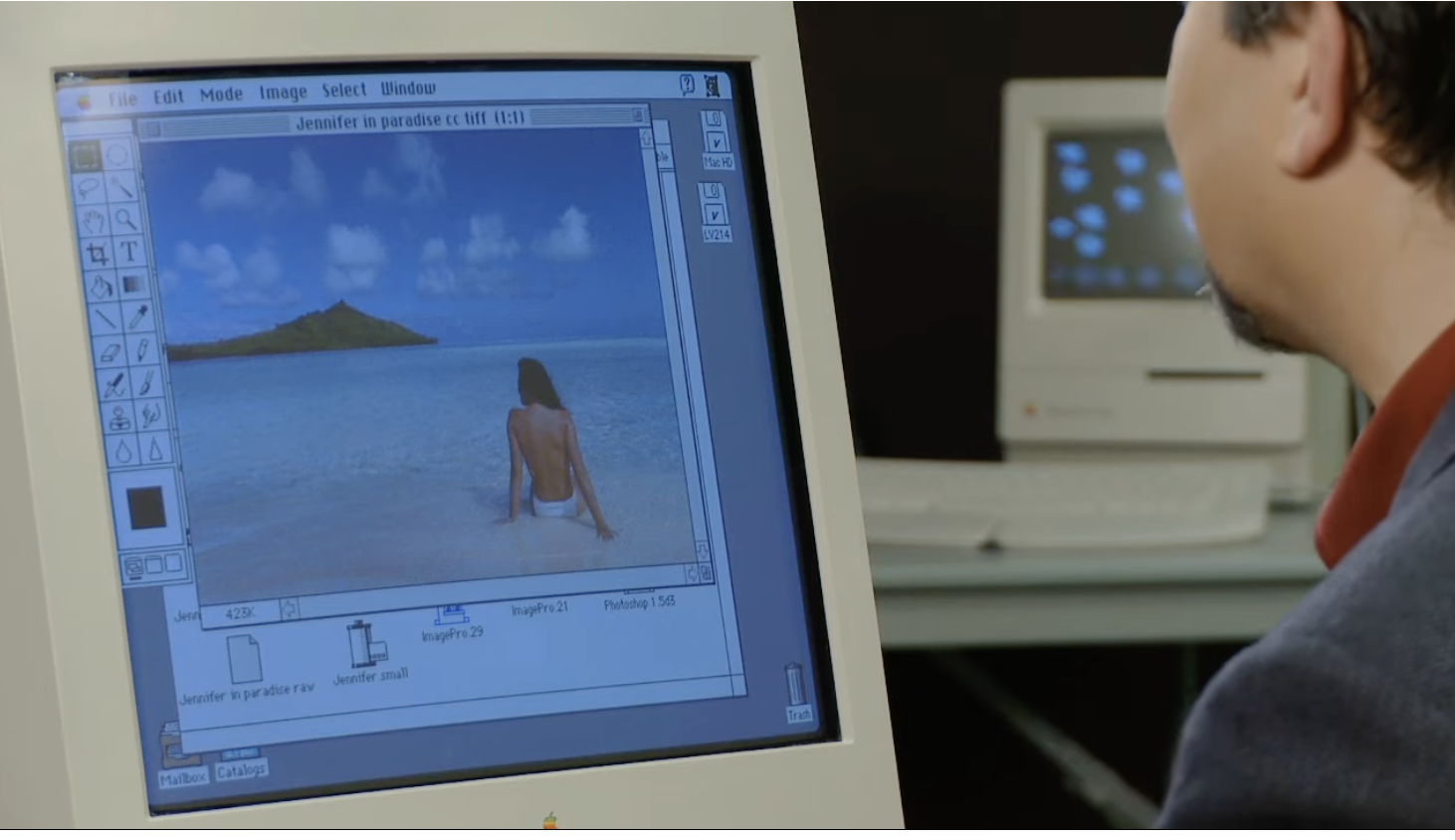

Then came visual interfaces. The Xerox Alto (1973), the Macintosh (1984). They brought the bitmap screen - pixels you can paint anything on. Suddenly you could do things that were basically impossible with command lines, like photo editing, desktop publishing, 3D CAD. We stopped designing around technological limitations and started designing based on the intuitive representation of the task. Icons meant things. You could point at stuff. Applications visually recreated the real world enabling mass adoption and creating the modern field of UX.

Agents reached this stage in 2024 with computer-use and browser-agents - Atlas, Comet, Claude for Chrome. Still early, none perform reliably yet.

Diversification

Now we're living through a diversification of interaction mediums, all optimised to integrate seamlessly into different aspects of human nature. Glasses, watches, phones, pins, earbuds, tablets, brain-interfaces. We've brought computing to our quirks - made it natural to have a computer for running, for driving, for cycling. We've made computers so naturally intuitive, viciously polished away every minute agitation, that one year olds who can't speak can use an iPad.

For agents, this stage remains underexplored. Just as you wouldn't use a desktop as a running computer, or an Apple Watch to do PCB design - agents will need many novel interfaces, tailored to specific tasks and to their unique quirks.

Fixed Function

Our earliest computers could only perform fixed actions. The Hollerith Tabulator (1890) added and subtracted, counting census cards. The Dreyer Table (1912) integrated, multiplied and divided numbers, calculating naval gunnery firing solutions. Results appeared on classical interfaces - dials and mechanical counters - the display was as fixed as the functionality.

Agents reached this stage in 2023 with tool calls - ChatGPT Plugins, function calling APIs.

Programmable

Then we invented programmable computers: ENIAC (1945), UNIVAC I (1951). You could write an arbitrary program, run it, and receive your results printed onto reams of paper and flashed through bulbs. We escaped the limitations of fixed interfaces, but state didn't persist. If you want to build on what you did, you're basically starting over, or you're manually copying outputs into new programs.

Agents reached this stage in 2023 with Code Interpreter, Claude Artifacts.

Interactive + Persistent

Then came interactivity, composability and persistence. The PDP-11 (1970), Unix (1969). Digital text displays and operating systems that merged the punch card UX (for writing code) and the paper printer UX (for reading outputs) into a single visual interface. Small displays meant every single character had to count - we designed UX where nothing was wasted. Command lines gave us composability: feeding one program's results into another, avoiding manual reading and rewriting. File systems gave us persistence: you could come back and work on tasks days later and your files were still there. Folders and directories gave us structures that humans intuitively could work with.

Agents reached this stage in 2023 with long running agents using bash, file systems - Cursor, Claude Code, Codex.

Visual Interfaces

Then came visual interfaces. The Xerox Alto (1973), the Macintosh (1984). They brought the bitmap screen - pixels you can paint anything on. Suddenly you could do things that were basically impossible with command lines, like photo editing, desktop publishing, 3D CAD. We stopped designing around technological limitations and started designing based on the intuitive representation of the task. Icons meant things. You could point at stuff. Applications visually recreated the real world enabling mass adoption and creating the modern field of UX.

Agents reached this stage in 2024 with computer-use and browser-agents - Atlas, Comet, Claude for Chrome. Still early, none perform reliably yet.

Diversification

Now we're living through a diversification of interaction mediums, all optimised to integrate seamlessly into different aspects of human nature. Glasses, watches, phones, pins, earbuds, tablets, brain-interfaces. We've brought computing to our quirks - made it natural to have a computer for running, for driving, for cycling. We've made computers so naturally intuitive, viciously polished away every minute agitation, that one year olds who can't speak can use an iPad.

For agents, this stage remains underexplored. Just as you wouldn't use a desktop as a running computer, or an Apple Watch to do PCB design - agents will need many novel interfaces, tailored to specific tasks and to their unique quirks.

That progression took humans a century. Agents have speedrun the majority in just three years. As AI capabilities improve, agents will get better at every tier - but just as you wouldn't run AutoCAD on an iPhone, agent UX has to suit the touch points they interface with.

And today, that medium isn't physical taps - it's text, with the occasional very expensive image. This is why AX is mostly about representation: crafting the interface to be transparent. Alan KayFrom Kay's 1989 essay User Interface: A Personal View. (reflecting on McLuhan's Understanding Media) put it better than I could back in 1989: "The most important thing about any communications medium is that message receipt is really message recovery: anyone who wishes to receive a message embedded in a medium must first have internalised the medium so it can be 'subtracted' out to leave the message behind."

Communication isn't transmission - it's reconstruction. The receiver doesn't passively receive a message; they actively rebuild it using internalised knowledge of the medium's conventions. The medium itself must become invisible (subtracted out) for the message to appear.

Hudson's cross‑cultural perception workThe test used drawings of a hunting scene: a man, an elephant, and an antelope. People with high photograph exposure saw the smaller elephant as "farther away." Those with little prior exposure saw it as "a small elephant" - same distance, different size. Neither is wrong. They're different learned conventions for decoding 2D into 3D. Hudson's 1960 study. is a clean example. Show a photograph to previously uncontacted humans and they'll struggle to understand depth in them - to discern if one object was in front of another. However when you personally look at a photograph of a man in front of a mountain, you don't see "coloured patches arranged on a flat surface with smaller patches near the top." You see depth, distance, scale. But that's only because you've so thoroughly internalised photographic conventions (linear perspective, relative size = distance, occlusion = in front of) that you subtract them unconsciously and perceive "the scene." The medium's logic colonizes your cognition.

Text is the medium models have subtracted.

They don't see tokens - they see meaning, structure, intent. But they've done it in a different way to humans. You'll find this hard to read: | Name | Age | Role |\n|------|-----|------|\n| Alice | 30 | Engineer |\n| Bob | 25 | Designer |

…but to a model it’s already organised:

| Name | Age | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Alice | 30 | Engineer |

| Bob | 25 | Designer |

Why? Because they were trained to imitate patterns like this until decoding markdown became automatic - dedicated circuitry that makes the medium disappear.

Leopold Aschenbrenner coined "unhobbling"From Aschenbrenner's Situational Awareness: The Decade Ahead (June 2024). He predicted ~2 orders of magnitude to effective compute have been contributed by unhobblings such as: chain-of-thought prompting, tool access, and the shift from chatbot to agent. to describe removing barriers that prevent models from applying their intelligence. That's all good AX is.

The intelligence is already there. Opus 4.5, Gemini 3, GPT 5.2 can all solve IMO problems.In 2024, the best AI scored 28 (silver). In 2025, both Gemini Deep Think and OpenAI hit 35 - solving 5 of 6 problems within the 4.5-hour time limit. They can write production code. They can reason through complex multi-step plans. What they can't do is suck in the world through a plastic straw.

Your job as an AX designer is to stop doing that.

A Framework for Agent Experience

Leveraging this understanding, I'm proposing a framework here - it's not trying to be complete but to hit on the points that matter.

I think there are basically three things you need to get right. What does the agent see? What can it do? What world does it live in? And for all three you're asking: how can you unhobble this for the agent? Have you made this unnecessarily hard?

If you’ve done UX before, this will feel familiar: Don Norman’s principles - the gulf of execution: can I figure out what actions are possible and how to do them? The gulf of evaluation: can I perceive what happened and whether it worked?We can go further than Don Norman’s principles and map out many of the most common UX terms against what is their most likely UI counterparts:

Additionally we can map out UX methodologies: User studies for example:UX equivalent AX equivalent Affordances tool APIs, command surfaces, permissions, action granularity Signifiers tool names/descriptions/examples, “when to use this” cues Feedback validators, tests, structured errors, observable effects Constraints schema validation, safe defaults, rate limits, guardrails Information architecture what’s in context vs behind search/read, progressive disclosure Usability testing task suites + trace review + intervention counts Time-on-task wall-clock + tool latency + number of turns + token spend Error recovery retries, rollback, checkpoints, diff/patch workflows Onboarding system prompt + tool primer + a few canonical examples

For the next few paragraphs you can imagine this simple mental model of an agent. The harness determines what the agent can observe, what actions it can take, how quickly it sees the consequences, and what state persists across iterations.

Agent reasons

"What's the weather in Tokyo?"

I need to call the weather API to get current conditions.

Surprisingly the majority of "agent failures" are not model failures. They're failures of the above loop: the agent is flying half-blind, acting through a keyhole, and getting feedback too late to course-correct.

Environment: What World Does the Agent Live In?

Late in 2025 many coding agents added Playwright, a tool enabling them to interact with the web, visualising the changes they made instead of coding blind. For many, I witnessed their agents suddenly run for over an hour instead of ten minutes. This is the power of verification. Agents with the ability to check their own work, to perceive issues, and to continue agentically looping when they would have previously thought a task complete.

The model didn't change, it was always that capable. It simply was operating without the signal it needed.

So if we could grant equally adept harnesses to other professions, what would we see? Comparing AI "software engineering" intelligence vs other professions gives us a hint:Based on the latest GDPval scores inclusive of Opus 4.5, Gemini 3, and GPT 5.2. See OpenAI Evals (GDPval).

And yes, the investment into coding is disproportionately higher, labs intend to automate AI researchers. However, I suspect the percentage of coding work automatable today actually lags behind other lower-complexity sectors. Look at customer support, sales managers, and editors above, the models have demonstrated their intellect, how much of this gap is simply underinvestment into profession specific harnesses?

With that said, coding has natural verification. Tests pass or fail. Code compiles or crashes. The browser shows something or it doesn't. In many other domains - writing, legal analysis, strategy - there isn’t an equivalent, fast, machine‑checkable signal. Quality lives in human judgment, which requires a person inside the evaluation loop.

So to take advantage you must transform your domain to have coding-like verification.

Legal review? Automated validation - citations, cross-references. The agent can attempt, fail, observe, and attempt again. The debugging instincts transfer. Market research? Frame as data analysis with test cases. Given these inputs, output should match these known examples.

The domain knowledge stays the same. The interface transforms into one where more verification is possible - where you borrow the reinforcement the model already has. Coding is the most heavily post-trained domain. When your task looks like coding, you're not teaching unseen skills, you're simply using existing ones.

This is why AX design is fundamentally about problem transformation. There is a magical feeling when you walk your problem in-distribution, and your agent flips like a lightswitch from a lazy, argumentative village idiot into an IMO-grade, unrelenting problem solver.

However, doing this well will require persistent state. Without it, an agent can't come back to edit the word document, it have no record of what was tried, what did work, what didn't. The model is truly hobbled. Implementing persistance needs to be done carefully, teaching an agent to use a custom ERP is just another hobble. Give it a file system, database, git; tools already seen in training data that are understood and recognised.

If done right persistence will unhobble further: adding version control enables checkpointing and rollback when things go wrong. Adding collaboration enables multi-agent work - branching, merging, and collisions. Adding todos enable long horizon tasks - escaping context decay and keeping agents on tasks for hours. Even adding the automatic saving of past chats to files - unhobbles the agent from having to perform the same mistakes over and over again.

Action: What Can the Agent Do?

When you design actions you're really designing an action surface: the verbs the agent has available, the granularity those verbs operate at, how well outputs can flow into the next step, and how retry-safe everything is.

And then you're designing how that surface is used over time: how actions combine into work, how the right action gets selected, how long-running work continues in the background, and what comes back from each action to make the next decision obvious.

This is why execution patterns matter. Most agent harnesses unintentionally force a single pattern: long sequential chains. Read some output, think on it, call the next tool, think on it. It "works," but it's like making someone build a house by carrying one brick at a time - most of the effort goes into transport, not construction.

The intent is not to provide an ontology of all execution patterns, but to highlight the tradeoffs in AX design you have to consider:

- Sequential tends to align best with today's training priors. For short tasks it can perform well, but it stacks latency and encourages manual transfer.Manual transferWhen the agent reads output from one tool, holds it in context, reformats it, and feeds it to the next tool. Each hop burns tokens and risks corruption. Compare to Unix pipes where data flows directly between processes without the shell touching it.

- Parallel collapses wall-clock time for independent steps, and avoids the back-and-forth overhead of an API - but it doesn't necessarily reduce tokens, and can flood context.

- Delegation enables dynamic computeDynamic computeAllocating model resources based on task complexity rather than using the same model for everything. Simple subtasks go to cheaper/faster models; hard reasoning stays with frontier models. The parent agent becomes an orchestrator, routing work to appropriate compute. and context saving: simpler subtasks can go to cheaper/faster models, which can absorb the messiness of doing exploratory or token-heavy work, returning summaries instead of raw dumps.

- Composition solves manual transfer: push predictable routing and formatting into a sandbox/programmatic layer so the model spends tokens on judgment.

Let's take two simple, ubiquitous tools as a case study: read_file and edit_file.To illulstrate I'm writing an editorialised history of challenges that Aider, Cursor, Cline, Roo, Claude Code, and Codex have built on eachother to navigate.

If there is interest in the future I may write a full history. And for those who want to learn more I would reccomend you read Paul Gauthier's edit format research, at the time he rigorously benchmarked these tradeoffs. However with today's frontier models - they can handle most sensible code diff representations - but the underlying AX principles remain.

Most take an obvious approach to start. read_file takes a file_name and returns the text content. edit_file takes a file name, a find and a replace string and applies an edit. You test and find issues: reading big files kills the agent instantly with context-overload - performing edits overreplaces (all instances of "100," even substrings like "100,592"). So you brainstorm: the agent need more granularity. You decide on adding line number specificity - read_file can be given a start line and an end line to read from, and edit_file must be given a line number where the find/replace starts.

Confusingly your plan fails, you discover that agents can't count lines! More than a few hundred and they get consistently confused. So you try a different move: make read_file start every line with its line number. You test again and now edit_file works reliably.

Then the second-order effects show up. You discover that a third of the agent population, those grown in OpenAI's reinforcement learning environments have different behaviour. Almost similar to how different countries teach different ways of performing the same tasks (e.g. long division, ...) - OpenAI's agents have learnt to edit files by writing and running python scripts with regex blocks. Every time they attempt it - failure - because it's attempting to edit what read_file returned, and what read_file returned now contains line numbers that don't exist on disk.

Worse, you've quietly broken composability. Before, the agent could do something like read_file(settings.json) and pipe the result into jq, or pass it into another tool that expects valid JSON. Now the line-number prefixes have turned your JSON into "JSON plus noise," and a whole family of tool chains stop working.

The AX principles here are simple: we solved it in the 70s - make "what you see is what you get" - ensure reading has the same interface to writing. Try and push any necessary interpretation layers down from actions into the environment, so all actions act on consistent representations.

However, this means we're back at the original problem: overreplacement. To solve we need to lean on classic UX thinking - which is not to have the user to type in the correct line number, but to popup a window surfacing the consequence of the action and let them steer. Say "this will replace 3 things, did you intend to do that?". This UX pattern is possible in AX via action feedback. When find has more than 1 match simply don't take the action, return the popup text, and provide a parameter for calling again that says "yes, I did intend to".

Ok, we've solved simple text files, but as humans we also need to edit videos, slides, documents, and unsurprisingly our read_file and edit_file interfaces aren't going to suffice. We need specific, targeted interfaces. And this introduces us to an interesting new challenge, there's hundreds of types of files, each with their own optimal AX toolkit, but each we include will burn context, cost more, and create confusion for our agent.

So just as you'd search for a editing tool to create a logo for your company, agents need a mechanism to search, and progressively discover tools. And just as you’d watch a YouTube video or read the instructions on how to slice your 3d model to print, agents also need searching learning and onboarding materials. Good AX is good UX in this sense, investing in optimising rapid onboarding, creating tight learning loops, all will unhobble the agent in your tooling.

One additional acknowledgement we need is that of time. All our execution patterns earlier conviently ignored it - humans don't stop acting when the video is rendering for 25 minutes; they context-switch, they start something else, possibly go interrupt a colleague, they come back when he spinner stops. Practically this means your AX must support synchronous and asynchronous tasks, alongside interrupts. Great AX protects flow state, minimises interruptions, mirrors human workflows, and when an interrupt does happen lands it at a safe boundary rather than shattering whatever loop the agent is in.

Conversation

Background Tasks

Background Agents

The diagram above is a clean representation of that split: conversation continues while long-running processes and autonomous sub-tasks run beside it. The important thing isn't the AX chrome; it's the lifecycle. Background work needs handles: start → running → progress → result → cancel. "Check progress" and "Get results" must be cheap, must be queryable, and must be saved to suvive compaction. Models will progressively take advantage of asynchronous work if you provide them with the right AX.

Perception: What Does the Agent See?

A human spends three hours reading documentation - building momentum, developing intuition, forming a mental model. An agent reads the same documentation - accumulates 100,000 tokens, scatters its attention across everything, and gets stuck on tangents.

This is the perception asymmetry: for humans, more reading often means better understanding; for agents, more context often means worse reasoning. Context shouldn't be thought of as storage - it's working memory under continuous pressure. Irrelevant tokens compete for attention, and introduce false options.

The solution isn't "give less information." It's to treat perception as a design surface with equal care to action or environment.

You don't read a hundred papers cover-to-cover to write a literature review - you skim abstracts, check citations, deep-read the three that matter. Human perception front-loads structure: orient, locate, then commit. We navigate before we read. Agents don't. Given a document, they will read the whole thing. Unless you unhobble them with the affordances to do otherwise: progressive disclosure (create multiple levels of representation, let the agent see structure before content) and targeted search (let the agent query, then read only what's relevant).

This means concrete tools: list_files() before read_file(). get_outline() before get_section(). search(query) instead of "here's everything." The agent decides what to read based on structure, not by drowning in content.

You already know this intuitively. When you're holding a complex problem in your head, you're protective of what you let in. You don't check email mid-derivation. You don't open Twitter while debugging. Irrelevant input corrupts the workspace, and displaces what you were holding.

Agents have the same vulnerability, amplified. Context is their entire working memory. And unlike you, they can't selectively forget - every token persists, competing for attention.

Reads everything first

Targeted approach

Human workflows often start loose and tighten over time - explore widely, accumulate material, then do the hard synthesis at the end. For agents, this sequence is backwards: it puts difficult reasoning at exactly the moment when context is most polluted and attention most scattered. Flip it. Front-load exploration and planning while context is fresh. Do the hardest thinking first.

This also argues for delegation. Spawn a subagent for the expensive read - let it fill its context with that one job, return a summary, terminate. The parent stays clean for the main work. Perception-heavy operations shouldn't pollute the context doing the reasoning.

Habituation - the dulling of attention through repetition - affects agents too. A human proofreading their own work misses typos because they see what they expect, not what's there. An agent repeating the same actions tens of times across inputs has strong inertia to always apply the same pattern - even for an input that's different. Good AX design accounts for this: rate-limit repeated signals, inject occasional false positives, emphasize novelty and deviation.

Familiar formats reduce friction. Markdown, JSON, standard schemas - these are already subtracted; the agent perceives meaning directly.This connects to linguistic relativity - the hypothesis that the structure of a language shapes cognition. For agents, it's not hypothesis but mechanism: models trained predominantly on markdown literally process markdown with dedicated circuits. Present the same information in an unfamiliar structure and you're forcing translation through general-purpose reasoning, burning capacity that could go toward the actual task. Novel structures force an extra translation step: decode the format, then understand the content. It's all training distribution. Present information in patterns the model has seen millions of times, and processing becomes automatic. Invent a clever custom format, and you're forcing general-purpose reasoning where specialized circuits could have handled it.

Beyond formats be wary that trust affects agent perception. You trust a friend differently than a stranger - models do the same. They're taught trust levels during post-training:

Without these boundaries, you get prompt injection - consider if you couldn't distinguish your own intentions from suggestions whispered by strangers. You'd act on every phishing email.Prompt injection is well-documented as a top LLM security risk. The attack surface is perception: external text enters through retrieval, tool outputs, or user messages and gets interpreted as instructions. Defense requires treating the perception boundary as a trust boundary. For humans we often give specific UX affordances "This site can't be trusted", sender verification badges, URL previews. Agent harnesses need equivalents: content tagging, authority markers, and sandboxed interpretation for anything that didn't come from the system.

Perception of change is difficult for agents, and it's taken to the extreme with collaboration: rapid micro-changes while an agent is attempting to work. For a human editing a shared document, they see cursors move, they watch text appear character by character - the interface surface changes as it happens. For an agent, they get snapshots. They read a file, reason about it, attempt an edit, and discover the file is no longer what they read.

Optimistic concurrency offers the easiest reliable starting implementation: when an agent reads a file, the harness remembers; when it tries to edit, the harness checks whether the file changed, and forces a re-read if so. But this ovbiously lacks the benefits of multiplayer like collaborative apps and the benefits of git like collaborative apps. There's a deeper principle open for exploration of how to make collaboration for agents; where change, history, and branching are first-class primitives.Ink and Switch's research on local-first software explores this problem space deeply from a human UX perspective. See their essays at inkandswitch.com, particularly "Local-first software" (2019), "Upwelling" (2022), and the ongoing Patchwork lab notebook.

We've Been Through This Before

When mobile arrived, we did what we always do: we ported what we had. The New York Times on the original iPhone was a desktop website you could pinch and zoom. It technically worked. It was also miserable.

It wasn't until we stopped asking "how do we put the web on phones?" and started asking "what can phones do that desktops can't?" that mobile became transformative. Phones had GPS. They had cellular everywhere. They had touch. They were with you. Designing for those native capabilities gave us Uber, Instagram, Live Translation. Experiences that couldn't exist on desktop because they were built from the medium's actual strengths.Another poignant example is the "horseless carriage" phase. When cars first appeared, they looked exactly like carriages - just without the horse. High centers of gravity, wooden wheels, even whip holders. It took years to realize cars allowed for fundamentally different designs: low aerodynamics, pneumatic tires, highways.Or the electrical revolution. Early factories were built around a single massive steam engine with belts and shafts transferring power throughout the building - work came to the tools.

Electricity allowed the opposite: small motors at each workstation, bringing tools to the work. Resistance to the transformation was significant - factory resistance was about physical architecture, not capability.

We're at the same inflection point with agents.

The first generation of agent interfaces has been "human UX, ported." APIs designed for human developers. Screenshots meant for human eyes. JSON schemas nobody would want to type. They technically work. They're also fighting the medium instead of using it.

The question isn't "how do we let agents use our interfaces?" It's "what can agents do that humans can't - and what interfaces would let them do it?"

Agents can read 200,000 words instantly. They can hold entire codebases in working memory. They can run a hundred parallel explorations without losing track. They can work for hours without fatigue, restart from checkpoints without ego, coordinate without meetings. These are native capabilities. Interfaces that leverage them - rather than hobbling them into human-shaped workflows - will produce experiences we can't yet imagine.

What Comes Next

Feynman diagramsBefore Feynman's notation, a single particle interaction required pages of integrals. After, physicists could sketch the same calculation as a simple drawing - and the drawings could be combined, extended, debugged visually. Wikipedia. made quantum electrodynamics calculations tractable - not by changing the physics, but by finding the right representation. That's what good harnesses do.

We have an entire industry built around understanding human users. Heatmaps, session recordings, funnel analysis, page flow diagrams. Where's the equivalent for agents? Right now we have logging and evals. That's debugging, not the next Mixpanel, or the next New Relic.

I want to see agent state transition diagrams. Attention saliency maps. Context pollution maps. A/B tests on tool designs and prompt structures. Treat agents as users. Do product research on them. The gap between professions on that chart isn't capability - it's how much we've invested in understanding how agents actually work in each domain.

We are currently forcing a silicon intelligence to wear a "human suit" to interact with our software. I'm increasingly convinced there's an order of magnitude of capability locked behind agent experience design. Purely in the harness alone. So don't shy away from exploring, from building your own agent, and don't believe that anyone has worked out all the answers yet. We spent a centuary learning how to design digital interfaces for humans. This is only year three for agents.

I'm excited to see the experiments you build and the directions you explore. If you build a unique harness, please send me a screenshot @rob_kopel.

Oh, and go play You Are An Agent.